Better Blood Tests, Drop by Drop

Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering; Assistant Dean (Special Projects), Faculty of Engineering

Founding Member, The Young Academy of Sciences of Hong Kong

HKU Outstanding Young Researcher Award, 2016-17

Professor Shum’s team have developed devices using a technique called droplet microfluidics. These small plastic chips have tiny channels, about the width of a single human hair. They can hold even tinier droplets of blood, whose volumes could be one-billionth that of a whole test tube.

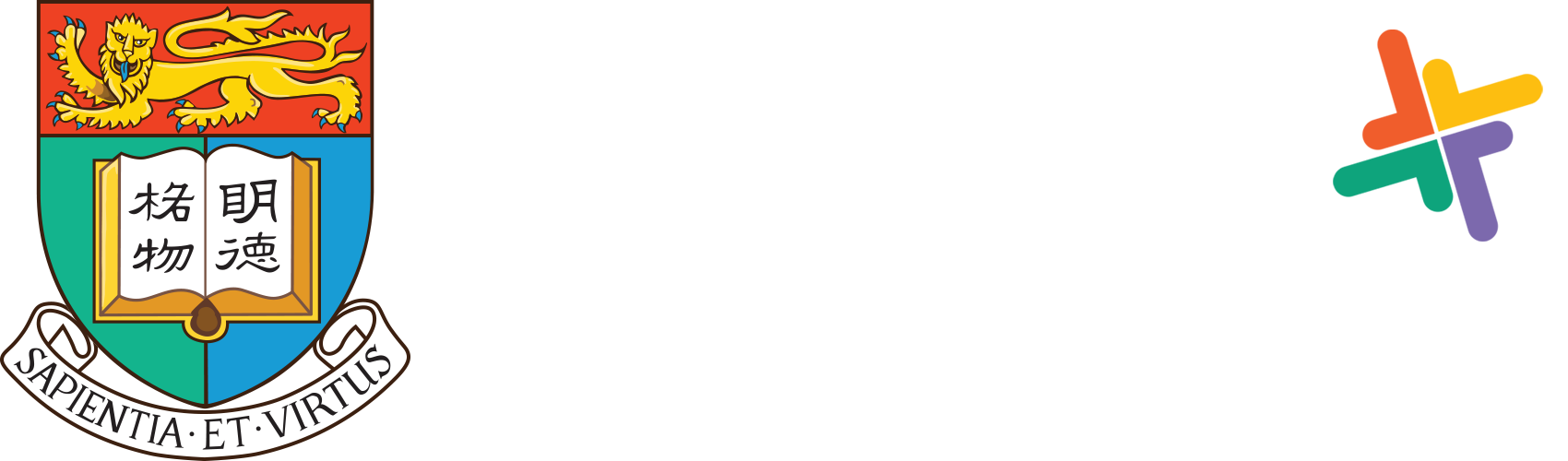

“We developed technologies to generate droplets at very high speeds – say, 1,000 droplets per second,” Professor Shum explained. “We can merge droplets, inject things into droplets, and detect what’s inside droplets.” Droplets can also be isolated and pulled out of the microfluidic chip for diagnostic purposes.

Professor Shum’s team have developed devices using a technique called droplet microfluidics. These small plastic chips have tiny channels, about the width of a single human hair. They can hold even tinier droplets of blood, whose volumes could be one-billionth that of a whole test tube.

“We developed technologies to generate droplets at very high speeds – say, 1,000 droplets per second,” Professor Shum explained. “We can merge droplets, inject things into droplets, and detect what’s inside droplets.” Droplets can also be isolated and pulled out of the microfluidic chip for diagnostic purposes.

Potentially, this technology could help researchers understand diseases better with data analytics. It could also mean that diseases could be detected faster and at an earlier stage, which would be a great benefit to patients.

Potentially, this technology could help researchers understand diseases better with data analytics. It could also mean that diseases could be detected faster and at an earlier stage, which would be a great benefit to patients.What next?

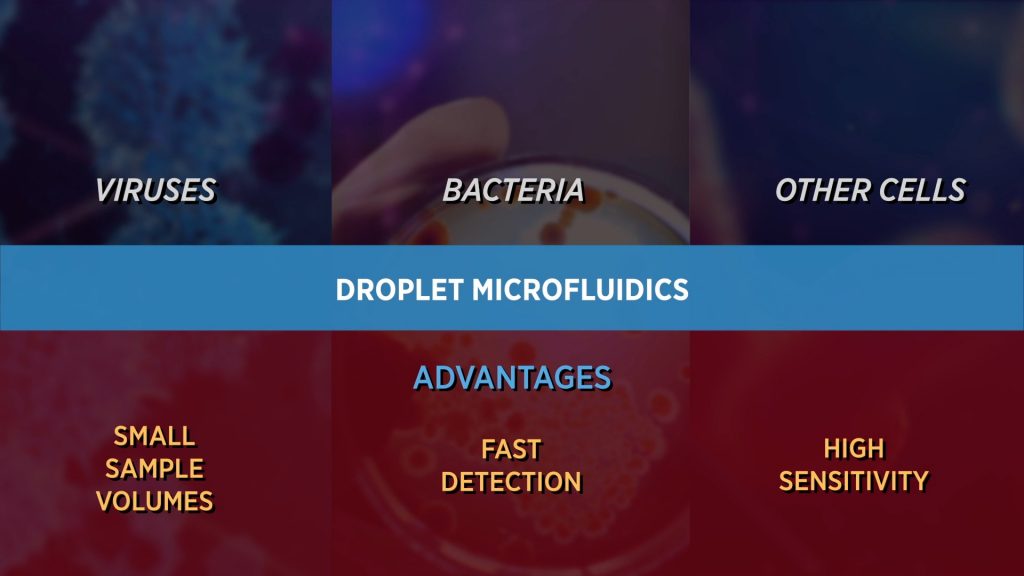

Professor Shum’s team have experimented using devices to identify viruses, bacteria and different types of cells.

They are already working with overseas collaborators at Princeton University and Harvard University – where Professor Shum did his undergraduate, and Master’s and PhD degrees, respectively.

However, more support will be needed so that this lab research can be turned it into medical instruments that can benefit the general public.

“Our research is highly multidisciplinary, requiring engineers, clinicians and industrial researchers,” Professor Shum said. He added that his team needed more modernised laboratory space, with set-ups for chemical and biological tests, as well as micro- and nano-fabrication facilities.

“Our vision is to improve healthcare, drop by drop.”